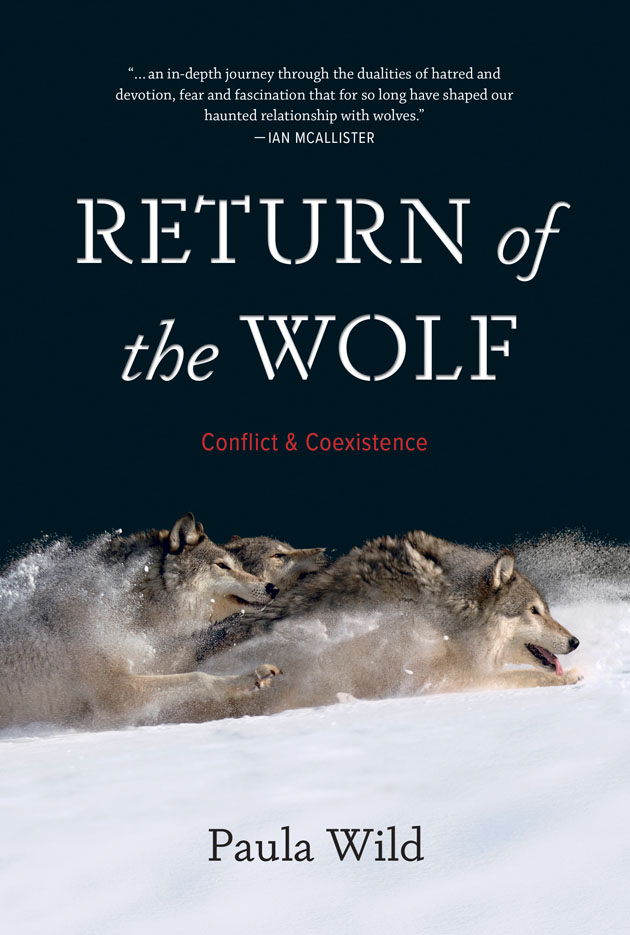

The Revelator, an online news source, recently compiled a list of 19 notable books about wolves. And Return of the Wolf, Conflict & Coexistence is included!

The books provide insight into the ever evolving relationship between humans and wolves throughout the centuries. Some focus on individual wolves and packs, while others explore the broader picture.

Most of the books are nonfiction but the list also includes novels and photographic collections, as well as children’s books and scholarly tomes.

Only two books out of the nineteen are by Canadians: Return of the Wolf, Conflict & Coexistence and The Pipestone Wolves: The Rise and Fall of a Wolf Family, a photography book by John Marriott, with text by Gunter Bloch.

The comprehensive list was compiled by John R. Platt, editor of The Revelator and psychologist, Dr. Colleen Crary.

To view this fascinating collection of books about wolves, visit The Revelator, Wild, Incisive, Fearless.

The Revelator, a news and ideas initiative of the Center for Biological Diversity, provides editorially independent reporting, analysis and stories at the intersection of politics, conservation, art, culture, endangered species, climate change, economics and the future of wild species, wild places and the plan