I was stuck. On page one.

Life stuff had halted my writing for months but today was the day I’d reclaim my real life. The only problem was nothing got better after the first page. In fact, the first ten chapters of the novel I was working on probably contained the worst words I’d ever written.

It was like getting into a brand new, shiny red Mercedes with black leather seats and then having a fissure crack open on all sides of the vehicle with no way over it.

I stewed, fretted and cursed. But no matter how much I stared at the page, I couldn’t get past this roadblock. Usually, a walk on the beach or in the woods clears the way for creativity. But there seemed no way back into this story.

In my 30+ years of writing, I’d never been this stuck before. It was like terminal constipation of the brain.

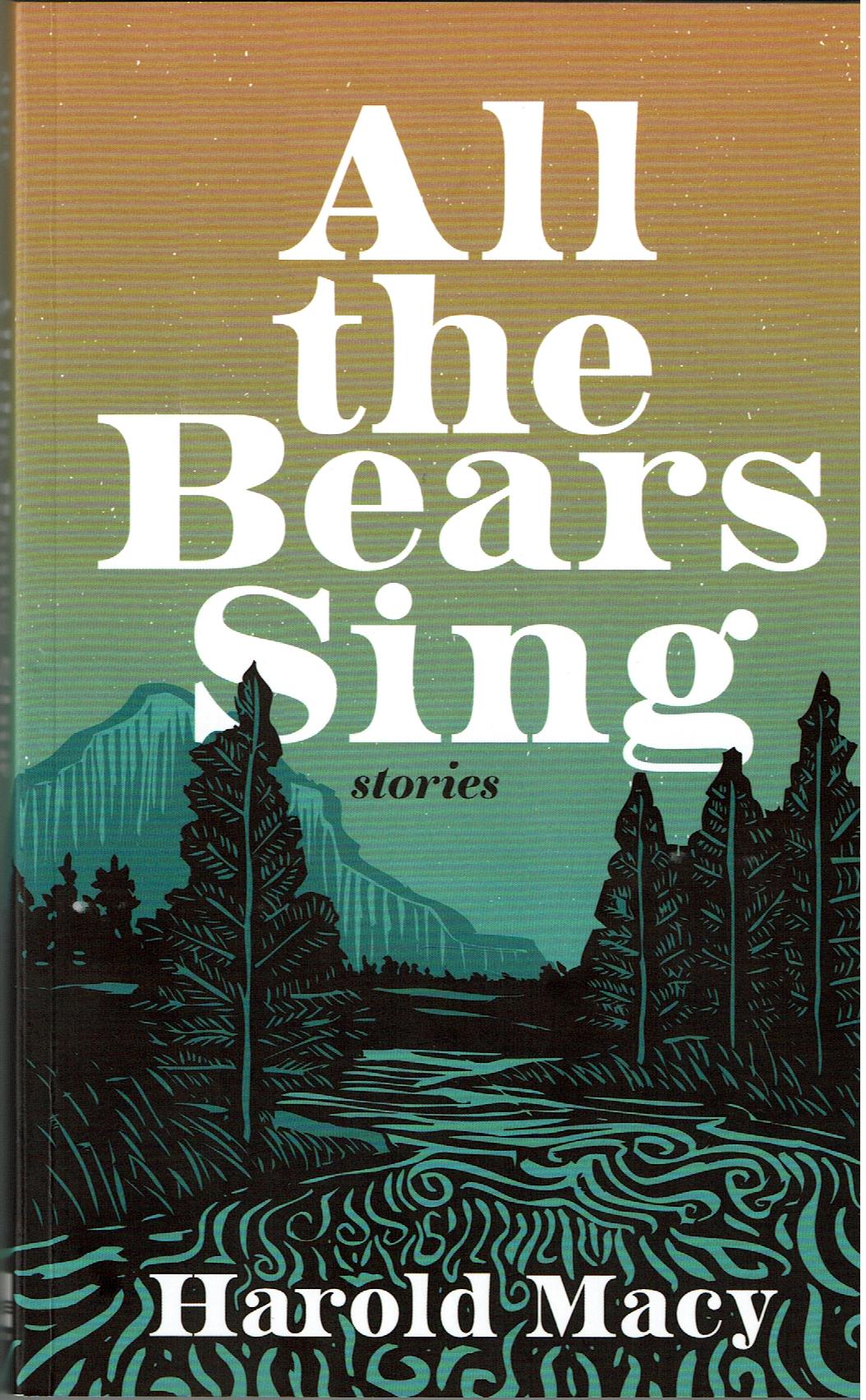

Finally, Harold Macy, a friend and writing colleague since my wanna be a writer days, told me to ditch starting at the beginning of the story and to just dive in anywhere. Another longtime writing friend, Caroline Woodward, said she was going to write 1,000 words a day for a month. I wondered if I could too.

Following Harold’s advice, I chose the climax of my story — where there was plenty of action and excitement — as my re-entry point to the novel. The energy was palpable and working backwards was eye-opening. I couldn’t remember if I’d set up events in previous chapters so it was always a surprise. It was almost like reading a book instead of writing one.

One thousand words a day – or even more – no problem. I was elated!

Then I got to chapter 10 and the red Mercedes screeched to a halt. The first third of the book still sucked. I felt like the guy in this photo — lots of ideas and all bad, bad, bad.

Then I got to chapter 10 and the red Mercedes screeched to a halt. The first third of the book still sucked. I felt like the guy in this photo — lots of ideas and all bad, bad, bad.

I was back where I started. But instead of a crevice, the Andes Mountains had sprung up in the road and there was no way over, through or around them. The problem was, I still really liked the story and didn’t want to abandon it.

I felt like a failure and wondered if I should give up writing. Be content with what I’d already accomplished. But, if I didn’t write, what would I do?

Then Derrick, a tai chi buddy, told me a story about one of his wife’s cats. I’m not a cat person but the couple’s struggle with Sophie stuck in my mind. A few days later I watched a 2003 Russian coming of age film, The Return.

A scruffy, doped up cat and two young boys adjusting to the return of their father was all it took. The mountains crumbled to dust and the Mercedes roared to life. I wrote a prologue and totally revised chapter one. The momentum kept up for revisions of the following chapters. After months of angst, I was writing again. And loving it.

So, what did I learn about dealing with a double whammy of a writing logjam?

-Be open to finding inspiration anywhere, on a bus, in the grocery store or in between moves on a checker board.

-Set writing goals and stick to them. The act of writing itself can shake something loose.

-Approach your story from a completely different angle, try working backwards, introducing a new character or changing a character’s point of view.

-Don’t be shy about sharing your woes and listening to suggestions.

-And perhaps most importantly, if you believe in your story, don’t give up.

Feature image credit: iStock 1085064170 Moussa81

Then I got to chapter

Then I got to chapter

intrigue and insight into the story of Danes attempting to settle the northern tip of Vancouver Island, as well as the beginning of a friendship that has lasted decades.

intrigue and insight into the story of Danes attempting to settle the northern tip of Vancouver Island, as well as the beginning of a friendship that has lasted decades.