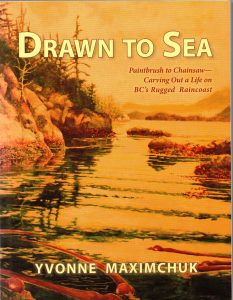

Drawn to Sea: Paintbrush to Chainsaw — Carving Out a life on BC’s Rugged Raincoast, by Yvonne Maximchuk is an intimate glimpse of modern day pioneering seen through an artist’s eye.

In the 1980s Maximchuk was a single mom living in White Rock, BC. She supported her two children by selling her paintings and pottery and teaching art. Then she met crab fisherman Al Munro. When Munro shifted to prawn fishing further up the coast, he invited Maximchuk, as well as Theda and Logan to accompany him.

Their new home — a float house only accessible by boat or seaplane – was anchored off Gilford Island in the Broughton Archipelago, a wilderness area east of northern Vancouver Island.

Maximchuk rowed her children to the to the one-room school and adjusted to life with a generator and the fact that the nearest grocery store was a two-hour boat ride away. She also soaked up the beauty and tranquility of the sparsely populated area, which soon infused her artwork.

But when Munro and Maximchuk split up, she faced a tough decision. Remain in the place she’d come to love or return to an easier life in the Lower Mainland? If she stayed, two major purchases were required: a chainsaw and a boat.

So began the challenge of being self-sufficient in an out-of-the-way pocket of the BC coast. Maximchuk was buoyed by the friendship of others living nearby including coastal icons Alexandra Morton and Billy Proctor. Proctor, with his “If I can’t do it, no one can,” attitude was especially helpful and always had whatever part was needed to fix anything and knew just how to do it.

When Maximchuk reunited with Munro, they bought land from Proctor and sweated and swore together as they built a truly handcrafted house. One that they still live in today and that now includes Maximchuk’s SeaRose Studio and a lush garden.

Drawn to Sea is an honest, affectionate story about love, the landscape and a gutsy woman finding her way in the ebb and flow of life. Maximchuk recounts the challenges and rewards of living and working in an isolated area and trolling with Proctor off the Queen Charlotte Islands. Nature and wildlife is never far away; she’s found cougars in her yard, been eye to eye with a killer whale and shared a finshake with a dolphin.

The book is funny too. I laughed out loud over the stories of Maximchuk dangling Proctor overboard in order to capture an especially large Japanese float, the kinks in her wedding day that failed to dispel the joy and one of her best Christmas gifts ever – an orange survival suit.

Maximchuk writes with a painter’s eye and a poet’s voice creating a richly rewarding sense of place, time and emotion. Drawn to Sea is a BC coastal classic that deserves a place on the shelf next to M. Wylie Blanchet’s A Curve of Time.

For more information visit www.yvonnemaximchuk.com.