What it was like:

The cardboard box sat on the floor beside the kitchen table for four years. I walked around it, passed food over it and occasionally shoved it around with the Dirt Devil.

Inside the box, the guts and soul of a book: a length of household string; a package of matches; a 2003 Telus calendar; a BC Interior road map; the Fall 2002 issue of GUSHER; handwritten pages torn from a Mead notebook; the first typed chapter of Campie. I’d started writing within days of leaving the oilrig camp in January 2003, opening with the declarative: “The job started with a fraud and ended with a lie.” (I loved that sentence.)

Oh, and one more thing was in the box: from the Saturday Post, April 19, 2003, an essay by Don Gillmore titled, “On Saturday Nights, I Dreamt of Saturday Nights.” Gillmore had written about his experience as a roughneck on an oilrig. I tucked it into the box to punish myself for not finishing the book.

What happened:

When I turned 50, I made a decision to stop feeling bad about my past. This meant retiring an aging inner blues trio called The Ambitions, Hopes and Dreams. “Sorry gals,” I said, “You gotta go. Momma needs a new tune … something like ‘Goodbye Alibi.’”

Six years later, I graduated from the University of Victoria with a BA and a book contract with Heritage House Publishers for Campie. The protagonist had become a Barbara persona distanced by a narrative arc in chapters.

I wasn’t me. Campie didn’t become a real book and my private story wasn’t public until I pressed SEND to the publisher. Not many nights later, I woke up in a sweat to a comeback choral performance of that sentimental oldie “Who’s Sorry Now?”

What it’s like now:

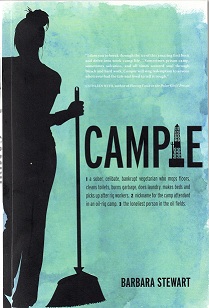

I came to realize that it wasn’t public exposure I feared at all. My motive for  writing Campie was to tell a story about failure and hope. The underbelly served a purpose. Although it took a few deep breaths to own the introduction, “a sober celibate bankrupt vegetarian …”

writing Campie was to tell a story about failure and hope. The underbelly served a purpose. Although it took a few deep breaths to own the introduction, “a sober celibate bankrupt vegetarian …”

No, it was the reaction of family and friends — those personally impacted by what I had written — whose love mattered the most. Unconditional acceptance by and for strangers was an easy grace.

When my sister said the book was so wonderful she couldn’t put it down, when my mother said she loved it and we talked about where it made her cry, when my daughter organized my first reading and invited her closest friends, when my son supported me for three months while I wrote and thanked me for all that I’d gone through, that’s when I knew I had projected judgments only within myself.

These Bessie Smith lyrics said it so well:

“Now all the crazy things I had to try, Well I tried them all and then some, But if you’re lucky one day you find out, Where it is you’re really coming from.”

Campie gave that luck to me.

Paula’s note: Barbara Stewart’s Campie, a new release by Heritage House Publishing, is the best book I’ve read in a long time. It’s funny, scary and brave. The writing is fresh and original; there’s no artifice or fancy maneuvering, just a great story told straight from the heart.

What a great write up. I could not have said it better myself. The bare naked truth is always far more amazing and inspiring than any fiction.

This is so honest and funny, the real deal. Some of us hide behind convoluted fiction for this very reason: to avoid getting closely related noses out of joint for real or imagined sins and especially to steer clear of maudlin, dumb-as-a-sack-of-hammers confessional crap about one’s own misspent youth, the stuff you don’t want your long-suffering mother or adolescent children to read about. It takes real guts to write about your life like this. I’ve now added Campie to my must-read list, and wish my late sister, who was a long-time oil and gas rig camp cook, was still alive to enjoy a gift copy. Congratulations, Barbara!