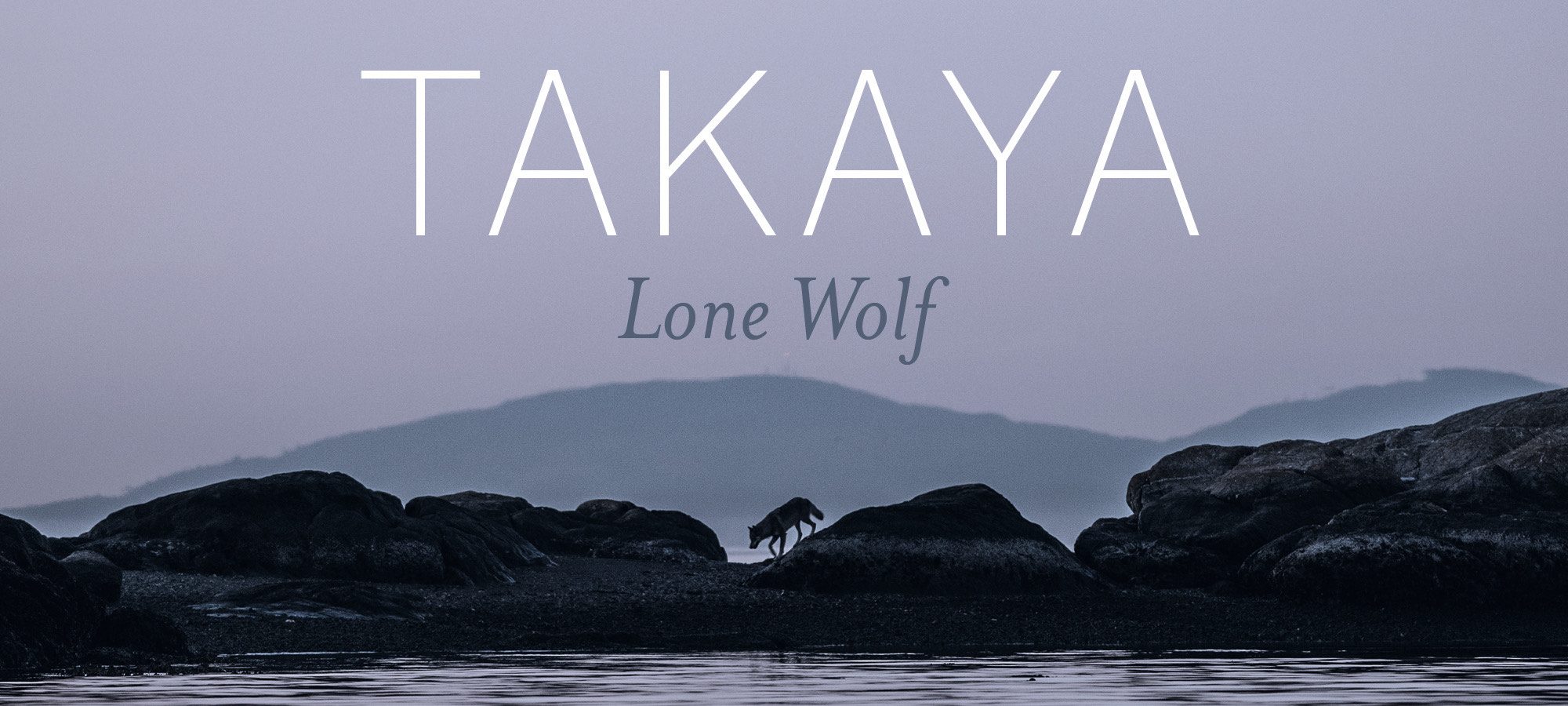

What does a wolf do when it finds itself in the middle of an urban area? Maybe daylight is seeping into the sky and people are stirring. The wolf’s instinct is to find a secluded, safe place. So, he plunges into cold ocean waters and swims a couple of kilometres through challenging currents to a small, rocky archipelago.

The wolf probably doesn’t realize this will be his home for the next eight years. A collection of islands with no deer to hunt, no year-round source of water and no other wolves.

He can see densely populated Oak Bay on southern Vancouver Island and hear dogs barking there. Sometimes he howls in return. He watches freighters and kayakers go by and learns to hunt seals, steal goose eggs and dig for water to survive.

But most of all, he learns to live alone. This is very unusual as wolves are highly social animals who live in family groups. No one thought the wolf would stay but, whether by circumstance or choice, he did. And thrived.

Takaya Lone Wolf is a story about a wolf and a woman. The first time Cheryl Alexander heard the wolf howl, she was hooked. The award-winning conservation photographer lived a short boat ride away and began watching the wolf she named Takaya. Personal observations and photographs were augmented by video footage and trail cameras. Before she knew it, she was documenting the life of a lone wolf.

Alexander’s new book provides an intimate glimpse into Takaya’s day-to-day life, as well as the vast beauty and richness of his domain and the wildlife that share it. The photographer’s persistence and patience also reveals some wolf behaviour that has perhaps never been documented before.

Takaya Lone Wolf is a beautiful blend of stunning photographs with heartfelt words. Alexander invites the reader into a wildness that, surprisingly, can exist close to the capital of British Columbia in Canada. It also raises questions about how humans relate to wolves. The book is scheduled for a September 29 release.

Last year, Takaya and Alexander’s story appeared on the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation’s The Nature of Things, as well as BBC TV in the UK and ARTE television in France and Germany.

For more information visit the Facebook page TAKAYA: @takayalonewolf.