Well, contrary to Susan and Harold’s experiences with book signings, I actually looked forward to my book launch of West Coast Wrecks & Other Maritime Tales with a good deal of confidence. Perhaps too much.

For one, I have no shortage of tasteful, better quality shirts in my closet. (Christmas presents over the years from Mom and also courtesy of Paula’s brother who manages the fashionable outdoor store, REI, in San Francisco). Plus I had just bought a new pair of black jeans. And since I don’t live in Merville like Harold, my fingernails stay reasonably clean.

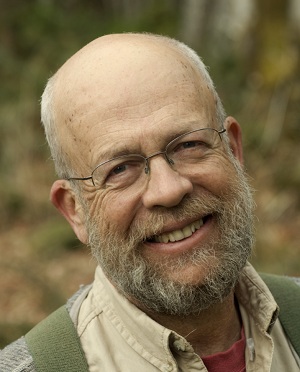

But I do make sure I get a haircut just before a presentation. Otherwise, my unruly, white locks tend to make me look like a deranged Albert Einstein.

Also, I credit my ability to stay relaxed before a group to the fact that I’ve given a fair amount of slide shows and presentations over the years. And for some bizarre reason, I’ve become a more social animal as I age and actually enjoy standing up in front of a group. (This been a surprise to Paula who often reminds me that I used to be a quiet and retiring Fanny Bay recluse.)

Last fall I had my book launch at the Vancouver Maritime Museum. And, gad sakes! some 60+ people turned up and they were all out there in front of me!! Man, I was pumped and I think my publicist from Harbour Publishing was surprised too. Turns out she misjudged the number of people who would attend and hadn’t purchased enough pastry items; a disappointment for those late getting to the goodies table.

The PowerPoint presentation went over exceedingly well. A good indication of success was the comments afterwards and question period that lasted for about 15 minutes. The worst thing that can happen at the end of a presentation is that everyone sits there with a deadpan, bored expression on their faces.

So I was brimming with an overwhelming sense of success and goodwill as I made my way to the book signing table where a crowd had already lined up. Then it happened; about seven signed copies along.

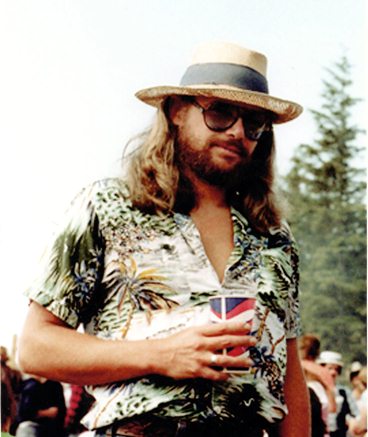

As I looked up at this big, middle-aged, balding guy with a pony tail I asked, “Who should I make it out to?” And he answers, “Rick James!” I did a double take and replied, “No, that’s me, the author, I mean, what’s your name?”

“Rick James!” he declared again. “Don’t you remember me from the old days in Victoria? How could ya forget, I mean, we not only have the same name…” And continues in an overly loud voice, “Oh man! We even used to smoke dope together at Keith’s place on Burdett back in the early 70s!”

Thankfully most of the folks around the table were old friends or work colleagues who were probably already aware of my past. Still, I could tell some people were startled. You know, the strangers I had managed to convince over the past hour that I should be looked upon as a respectable West Coast maritime historian and writer. Who knows what they thought after the other Rick James finished talking?

So there you go, no matter how well prepared – and groomed – a person is for a book signing, something totally unexpected can still bring you to back to reality with a jolt.