Wolf paws are the foundation for the carnivore’s every movement. They carry the predator across rugged terrain, serve as snowshoes in deep snow and provide traction on icy surfaces. And the heavy padding means a wolf can move across the landscape as silent as a cloud.

Of course, if a wolf is travelling across rocky ground or a paved road, their nails may click against the hard surface. Wolves have four toes on each paw, as well as another toe, the dew claw higher up on the front legs.

The structural dynamic of inward-turning elbows and outward-turning paws results in a highly efficient gait that puts little or no stress on the shoulders. And webbed toes mean wolves are capable of fording rivers, lakes and even up to thirteen kilometres (eight miles) of open-ocean.

Wolves possess an internal temperature regulation system that prevents their toes from freezing in northern locations. They also have scent glands between their toes, allowing other wolves to know if it was a friend or foe that passed by.

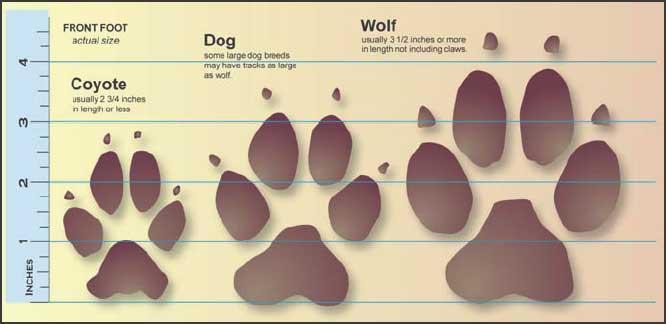

Wolf paw prints are generally recognisable due to their size – about 7.6 – 10 cm (3 — 4 inches) wide and 8.9 — 11.4 cm (3.5 to 4.5 inches) long on an adult. Some dogs, such as Great Danes or Blood hounds have tracks that are longer than wolves but most dog paw prints are smaller and rounder.

Coyotes have smaller tracks than most dogs and wolves. Young wolf pups’ paws grow incredibly quickly so, even at three months old, most wolves have larger feet than an adult coyote.

Top photo iStock/Ramiro Marquez